At the University of Minnesota College of Design, Madeline Juve and Mady Gulon are asking tough questions on material reuse and life-cycle assessments. Both are pursuing advanced degrees in sustainability and research practices, respectively, with focuses on material agency. I sat down with them to discuss the complex web of challenges beneath the simple idea of “reuse.”

Where do reclaimed materials go in between disassembly and new construction? This is one question that Madeline posed as a part of an inquiry into the larger question, “is reuse inherently good?” A surface-level glance at material reuse and life-cycle assessments (LCA) can overlook many challenges – like intermittent storage – that would prevent meaningful integration into current building practices. Increased energy use for dismantling, particulate matter, transportation impacts, and warranties are important considerations that Madeline is not finding in some life-cycle equations.

The specific material that Madeline is using to interrogate these systems is brick. Masonry is unique in its ability to disassemble and rebuild — when in good condition. If properly maintained, brick can last 500 years. Madeline sent me down a rabbit-hole of deconstruction videos, and all the drilling, chipping, and chiseling it requires. She also cited research for masonry walls made from cut-up chunks of recovered brick walls. The researchers found, as Madeline has, that the economics of reuse sometimes don’t add up; the cost of the reclaimed wall was double that of a new one.

Though, markets don’t capture everything. There is a qualitative reason for Madeline’s material choice — she simply loves brick. Growing up in the Midwest, and spending her undergrad years in Milwaukee, she has a strong connection to masonry. The vision of reclaimed brick architecture motivates her to find new lives for this beautiful material. These behavioral and emotional factors are often left off of our LCA spreadsheets - see Timothy Gutowski’s paper for more on this. There is an undeniable physical beauty that accompanies the environmental ideal of using material as long as possible.

Mady Gulon is also searching for beauty in the process - by reconnecting with her family’s vocation of forestry. While learning more about wood extraction by interviewing family members, she is searching for opportunities to turn Minnesota’s waste wood into new mass timber products. Her investigations have led her around the Twin Cities, collecting scrap wood of all shapes and species. In the wood shop, she breathes new life into the discarded by creating mass timber mock-ups for testing. These experiments have exposed some of the difficulties of upcycling timber - probably the reason it is easier to send most wood to landfills. Nails, defects, and non-standard sizes fill the salvage piles, needing extra work and thoughtfulness to reconfigure.

One researcher inspiring Mady’s projects is Colin Rose of the University College London - whose work on cross-laminated secondary timber (CLST) won the Flemming Bligaard Award in 2020. Rose estimates that over 1000 houses could be built every year from just a fraction of the UK’s annual wood waste. He has done extensive research on both the evaluation of material stock and the testing of actual CLST panels. Colin is also asking the difficult questions around wood upcycling: how moisture fluctuations impact secondary wood properties, what new waste collection networks are necessary, and what scale of operation is needed to be commercially viable. He is working to address the waste of today, while preparing to manage the waste of the coming decades. The EPA predicts that the US will see peak levels of wood waste by 20501, corresponding to increased consumption in the early 2000’s. All of this material will soon be entering the waste stream…the question is, what are we going to do with it?

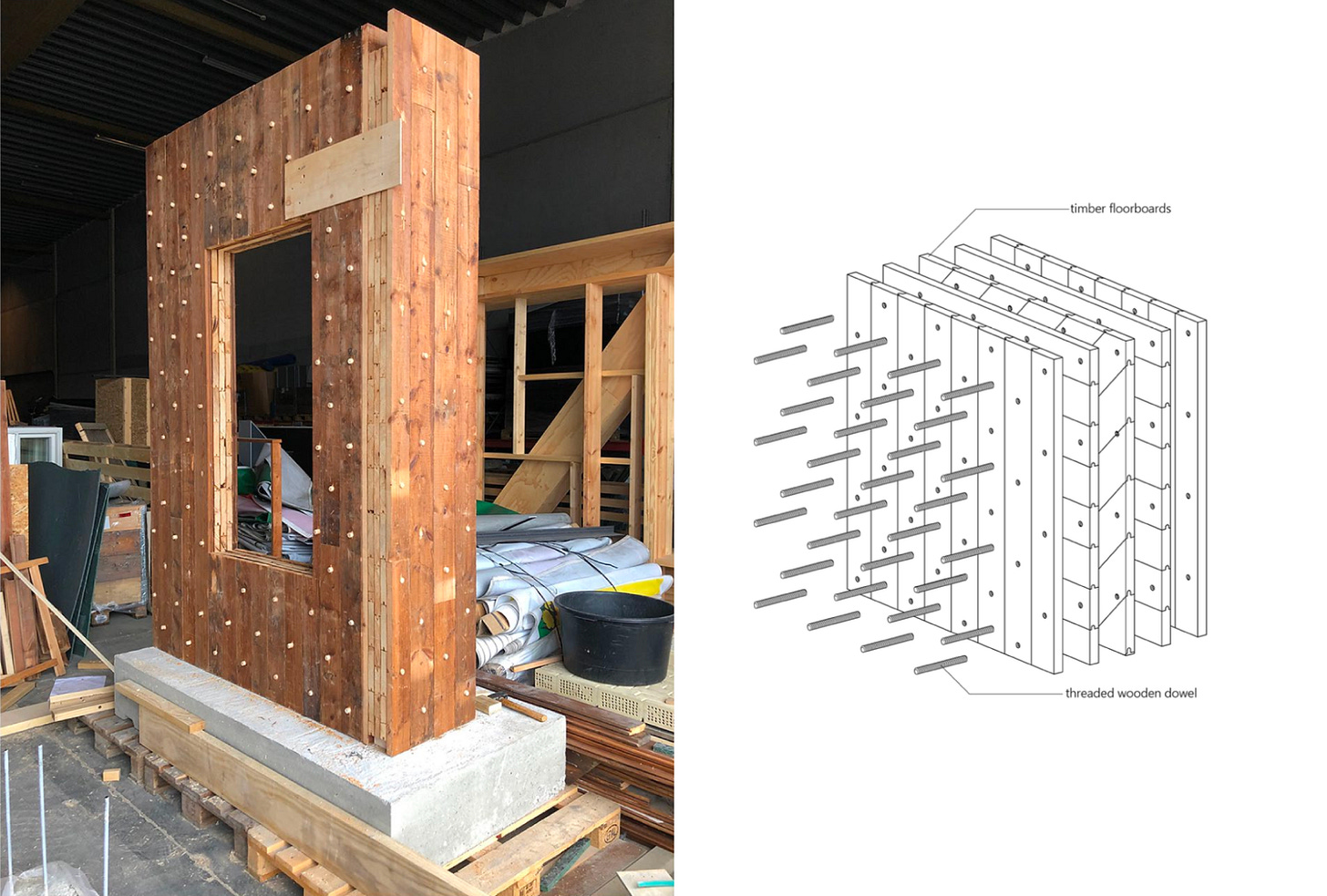

Mady also pointed me toward the work Xan Browne, who (along with Olga Larsen, Nikolaj Friis, and Magnus Kuhn) is building on Colin’s work to create mass timber systems from defective wood. The team created and tested a mass timber panel of discarded floor boards fastened with threaded dowels. The dowels mechanically connect the warped boards where glue couldn’t - meaning minimal processing was necessary to create the assembly.

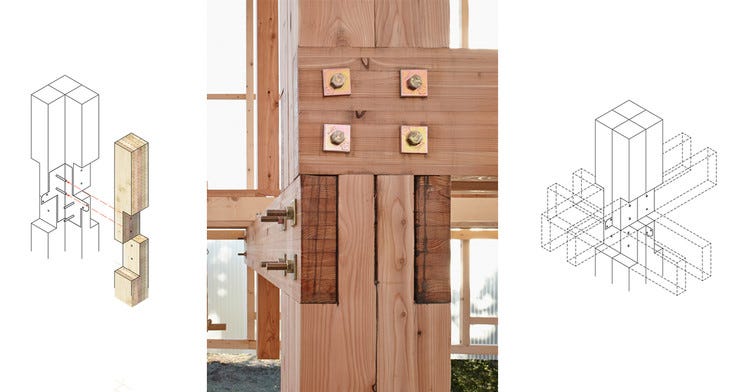

One crucial pinch-point that both Madeline and Mady emphasized was deconstruction. Madeline finds with bricks the same condition that Mady finds with stick framing, these systems were not designed to be dismantled. Deconstruction of current structural systems is time-consuming and costly. This reality leads to more down-cycling - pulverizing bricks for aggregate or shredding wood into chips - instead of extracting the maximum possible value. A concurrent movement called Designing for Disassembly (DfD) aims to make Mady and Madeline’s goals much easier in a few decades.

The University of Oregon and Oregon State University have done some fantastic research on mass timber DfD and reuse - along with all its complexities. Designing for disassembly requires careful planning and attention at all scales of building. The reward of diligence is that every year of service (multiple centuries for both materials) can be maximized. The concurrent task of redesigning waste systems to accommodate previous construction, while advancing new strategies to make future disassembly easier, is a fascinating architectural project across time and space.

Reuse is a messy problem – a tangled web of engineering, economics, and emotions. Madeline and Mady are up for the challenge. As Mady said during our conversation, “architects are collagers”. These two researchers are piecing together systems of beauty, ecology, and construction to create less-wasteful buildings. It is an exciting pursuit, and I cannot wait to see how their projects evolve.

Quote I’m Pondering

“...wind extinguishes a candle but energizes a fire. ‘You want to be the fire and wish for the wind.’”

- Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Jonathan Haidt, and Greg Lukianoff in The Coddling of the American Mind

What I’m Reading

“The Story Construction Tells About America’s Economy is Disturbing” by Ezra Klein in the New York Times.

The description: Klein lays out a few reasons for why construction productivity has been stagnant for fifty years - left behind by the rest of the economy.

See you next week,

Tom

US Environmental Protection Agency, Wood Waste Inventory: Final Report, Anthony Zimmer, Helena-Solo Gabriele, Keith Weitz, Aditi Padhye, Samantha Sifleet. 2018.