This past week, I continued my line of curiosity on the history of conservation by tearing through a book referenced in last week’s read (Down to Earth) titled, Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency: The Progressive Conservation Movement, 1890-1920 by Samuel P. Hays. In the book, Hays asserts that most histories of the conservation movement have it wrong.

The American conservation movement was born from a desire to better use and manage America’s natural resources, not protect them. Far from a grass-roots initiative – and independent of any widespread national values on nature preservation – conservationists were most focused on how to manage, plan and use America’s resources for maximum human benefit with minimum waste — i.e. maximum efficiency.

Efficiency was in the air at the turn of the century. Almost every aspect of life was under scrutiny as reformers looked to transform the dilapidated cities, poor working conditions and exploitation of natural resources into a model-machine of productivity. This cultural fascination brings to mind the birth of thermodynamics (specifically “entropy” as it relates to unusable energy and waste) happening around the same time – best described in The Birth of Energy. A gospel of efficiency also captured the minds of optimistic conservationists who “subordinated the aesthetic to the utilitarian. Preservation of natural scenery and history sites…remained subordinate to increasing industrial productivity.”1

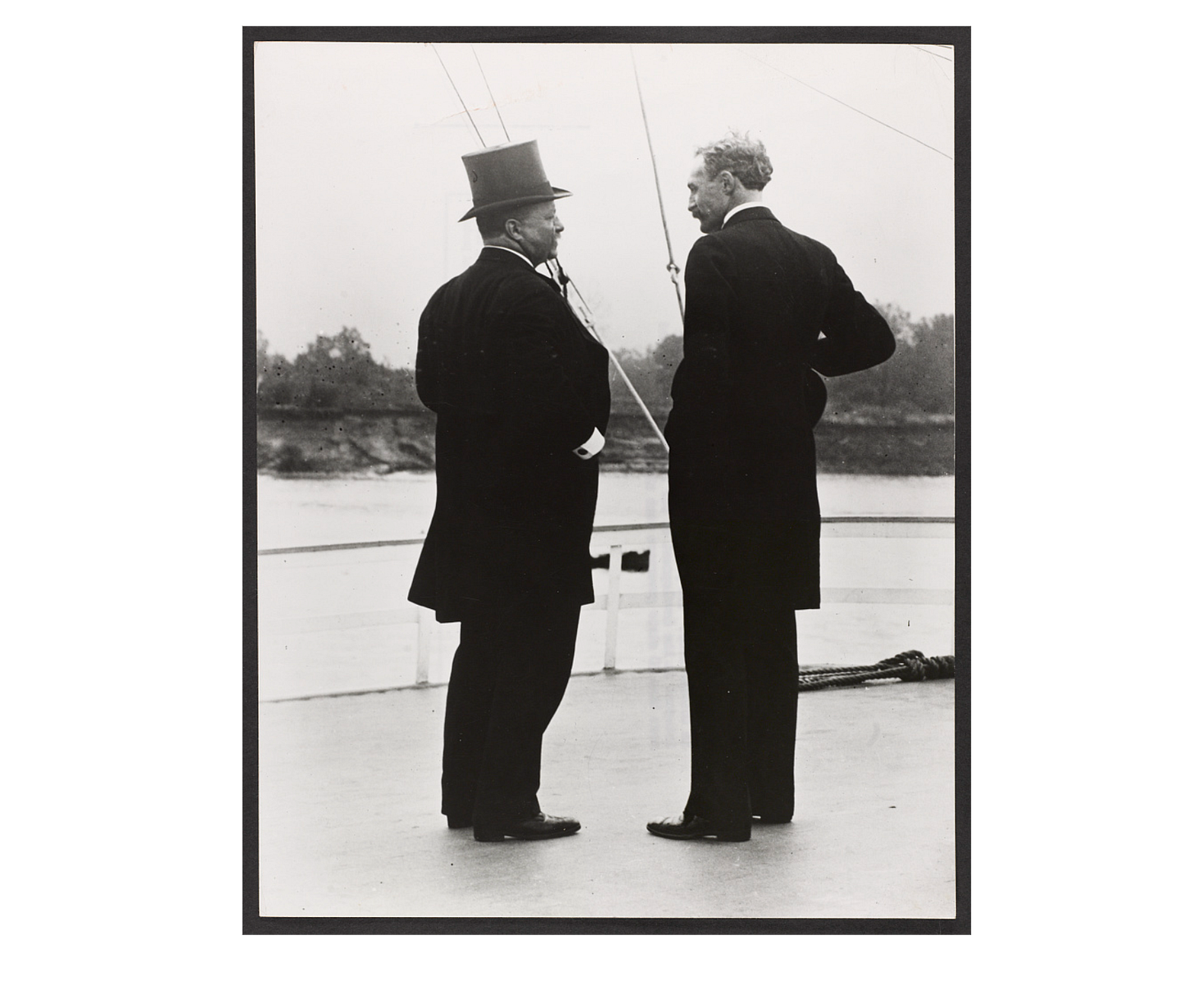

The leaders of this movement were wealthy, educated urbanites who looked in disgust at the land’s exploitation from 19th century entrepreneurs not because trees were cut down or the soil was disturbed; it was the waste. Opportunists had ripped seemingly inexhaustible resources from the land in the name of market demand and competition. America had developed a “tradition of waste.” Outdoorsmen, like Theodore Roosevelt, of the Progressive Era were appalled by the lack of direction in resource development. He and other conservation leaders believed that unrestricted economic competition only created waste, inefficiencies and exploitation. His solution to managing natural resources, and all other societal problems, was efficient planning by experts. Only those trained in the latest scientific management, using the most up-to-date technology, should determine the goals and methods of resource use. Not only would this heal the damages of past actions, it was the key to solving all social problems too.

One such expert was Gifford Pinchot – chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, first head of the United States Forest Service and right-hand-man to Roosevelt. Pinchot “contributed more than any other individual to public awareness of forestry and water power problems.” A pioneer of scientific forestry, he grabbed the reins of the government’s forestry programs to execute his vision for sustained-yield management of the nation’s woods. Over his prolific career, he never failed to stress the utilitarian value of the forests — especially in the face of “preservationists” who pushed for federal lands to remain untouched:

"The object of our forest policy is not to preserve the forests because they are beautiful...or because they are refugees for the wild creatures of the wilderness...but...the making of prosperous homes...Every other consideration is secondary."2

He’s a major character in the book as he is one of the movement's most important figures. His name today is synonymous with conservation and environmentalism though Hays uses the book to remind us how strongly Pinchot felt about proper development of natural resources everywhere, including National Parks. It was firmly against his wishes that parks were/are closed to industry — hence, why there is a difference between National Parks and National Forests. Pinchot’s views were shared by those spearheading the push for conservation: open the land to development under the proper expert management.

There was a swell in interest for conservation around 1910 when urbanites, enchanted with “rural life,” looked to the countryside and its “eternal values” from their dirty, disorganized cities. Nature provided the “regeneration of the human spirit” that these new apostles sought.3 The conservation enthusiasts were unified by a feeling that material gain was too prominent in America and salvation lay in the soil of the earth – “tinging the conservation movement with the emotions of a religious crusade.”4. Yet, a “wide difference in attitude” separated Pinchot and Roosevelt from the wave of new members. While their support and moral weight was helpful in swinging a hostile Congress, it became especially difficult to approach resource development or lawmaking when political support came from those more interested in reserving sacred landscapes from economic use rather than applying technology to their development.5 .

Roosevelt embodied a division and paradox in the retrospectively unified movement. He believed the good society was classless and agrarian yet was obsessed with efficiency and the modern technology of a highly organized industrial society. He and his administration used their offices to centralize, coordinate and execute national resource decisions without the participation of “the people.” Roosevelt’s contradiction, and the entire conservation movement, according to Hays, raised a fundamental question in American life: “How can large-scale economic development be effective and at the same time fulfill the desire for significant grass-roots participation.”6

I believe this question is still worth pondering…

The fuel that continues my dives into the history of conservation was/is a realization that these terms (conservation, preservation, sustainability, environmentalism, etc.) mean very different things. I had often packaged them together, with a blind stamp of approval, and shoved them forward as better then whatever “non-sustainable” alternative there was. But extending any individual idea into the future will create an entirely different world from the other, even if their starting points are shoulder-to-shoulder.

Better understanding what a conservationist was is helping me discern what “conservation” means today. This is relevant since, in 2021, the Biden-Harris administration created the American the Beautiful campaign (also known as 30x30) calling for the conservation of 30% of our lands and waters by 2030. It sounds great, but what does it mean? I read through the documentation, and even the report acknowledges the difficulty in defining the word (page 12 and 16).

These histories of wrestling over policies, actions and ideas about nature are helping enlighten a world-view that was all too binary. The conservation movement was not simply the grass-roots nature-lovers rising to the nation’s highest office to squash the industrial capitalists in the name of protecting nature. Rich with aisle-jumping, paradoxes and individual interests, the story is much more complex and this story, specifically, is well worth a read.

Note: All links to Amazon pages are affiliated with Emergetic and a portion of each sale comes back to us. Thank you for your support!

Samuel Hays, Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency: The Progressive Conservation Movement, 1890-1920 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1959), 127.

Ibid. pg. 42

Ibid. pg. 145

Ibid.

Ibid. pg. 146

Ibid. pg. 276