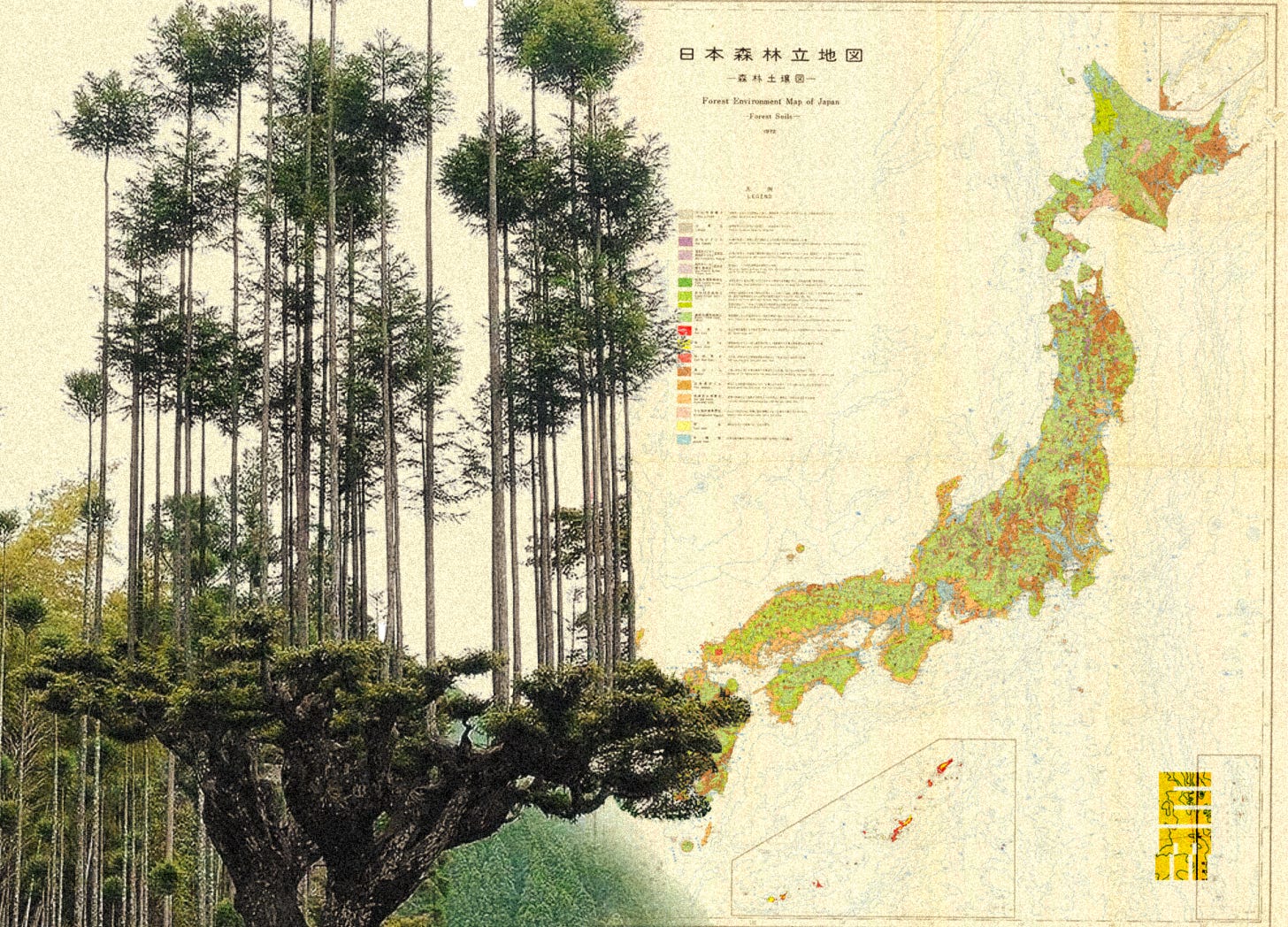

Last week, a surreal image stopped my scrolling thumb in its tracks. A small forest of miniature, arrow-like trees shot from a wide and gnarly trunk. It was surely photoshopped, I thought, but I kept reading. The post, from Jakob Strømann-Andersen (director of innovation and sustainability at Henning Larsen and a great follow, by the way) revealed this uncanny tree was the product of a 700 year-old Japanese forestry practice.

The technique, named daisugi, creates multiple straight timbers from a single tree through selective pruning – basically, creating a giant bonsai tree. The name roughly translates to “platform cedar”, because it only works on Japanese cedar trees (Cryptomeria japonica). The practice requires consistent trimming by hand, but the laborious work can produce hundreds of trunks from a single tree. The lumber from daisugi trees is said to be 140% as flexible as standard cedar, and twice as strong.

While the shoots are harvested, the trunk of the tree holds firm and continues to grow; its thriving roots retain their grasp on the soil. The routine pruning also lets more light reach the ground, meaning more grasses and smaller plants can take root around the tree’s base. This is a vital defense against erosion – one of the many dangers of reckless harvesting.

Before human intervention, Japan was almost completely covered in trees, but the extreme terrain of this volcanic archipelago left many of the forests unharvestable. Daisugi was developed to maximize output from cedars growing on the steep slopes – an attempt to meet the increasing demands of a nation completely dependent on its trees.

Material from the forests was used for building, burned as fuel, spread as fertilizer, fed to animals, and converted to charcoal - which smelted the metals used to make better blades for harvesting. Japan was constantly locked in a push-and-pull between forests and farmland – they only had so much room.

During the Edo Period (1603-1868), a boom in construction and population pushed the forests beyond their limits. Leaders requested ever grander temples and cities be built from more and more trees. Forests were converted to farmland wherever possible to feed more hungry mouths. There was a top-down push for locals to harvest as much wood as they could. The nation, isolated from global trade, exhausted their forests within a century.

Regenerative policies began to take hold out of sheer necessity. The country was dependent on the resources of the islands with no way of importing more. So, they started planting. The nation worked its way out of an ecological crisis by reforesting the country wherever possible. Plantation forestry took hold to meet ever-increasing demand.

By the 20th century, new industries and bodies of knowledge around forestry practices established a sustainable supply of forest products. Japan had ceased to rely on old-growth forests and found most of its demand met from replacement stock – an increasing amount of which came from plantations. This is because so much emphasis was placed on planting the most useful trees, i.e. “sugi” (Japanese cedars) — the kind fit for pruning. By 1950, Japan was 90% self-sufficient in lumber, and wood was still its primary fuel. By 1980, over half of all wooded areas were planted forests.

In his book The Green Archipelago, Conrad Totman emphasizes that acts like pruning and replanting were largely practical and not necessarily based an a cultural “love of nature”. Forest recovery was generally a means not an end. Japan’s monocultural emphasis pushed biodiversity to the sidelines since the goal was maximum yield. The negative effects of Japan’s “sustainable” efforts are a cautionary tale to contemporary planting operations.

The years after WW2 saw Japan’s most recent surge in replanting, but a flood of imports undercut the country’s own logging industry. Japan outsourced its deforestation to other countries while fewer and fewer people were left to care for the new forests at home. By 2000, Japan was importing over 80% of its lumber.

Japan’s forestry production has been in a steady decline, and its planted forests have become liability rather than an asset. Flooding and landslides are increasingly common from the single-age plantations, whose dense canopies create barren forest floors. Many species have been driven out of these unnatural habitats and a lack of falling deciduous leaves has thrown the nutrient cycle out of balance. While Japan was early to develop national policies of afforestation, it has been “slow to make the transition to environmentally oriented ‘new forestry’”.

These days, Japan is trying to increase its self-sufficiency, train a new generation of foresters, and emphasize biodiversity. Might daisugi have a roll to play in this new wave of forestry practices? Possibly. If anything, the ancient technique is window into centuries of forest experimentation. There is so much to learn from Japan’s unique relationship to wood through time. Maybe the history of Japan holds the seeds for the future of forestry, or maybe it is just a cautionary tale. More reading, and seeding, is required.

What I’m Reading

“The Wizard and the Profit: Two Remarkable Scientists and Their Dueling Visions to Shape Tomorrow’s World” by Charles C. Mann

The description: This is one of the most important books I have ever read. It is nearly impossible to summarize this page-turning dive into the history of our present-day environmental movement through the people who crafted it. There is so much here. Please, just read it!

“UN’s Climate Panic is More Politics than Science” by Judith Curry in Climate Etc.

The description: An important read following the latest IPCC report. It may not be as dire as the headlines say…

What I’m Watching

“California’s Redwoods Are Too Tall for Their Own Good” by Aidin Robbins

See you next week,

Tom